Ink and whiteout on paper

Silkscreen on acetate over etching

Etching, 25.75h x 24.75w in

Etching, 27.69h x 27.25w in

Brass plaque with mixed media, Variable size

Ink and whiteout on paper

Paper, 8.5h x 11.8w in

Mixed media, 19h x 10.5w x 2.3d in

Mixed media, Variables size

Mixtes media, Variable size

Fan, thread, and pencil, Dimensions variable

Ink and whiteout on paper, 11h x 8.13w in

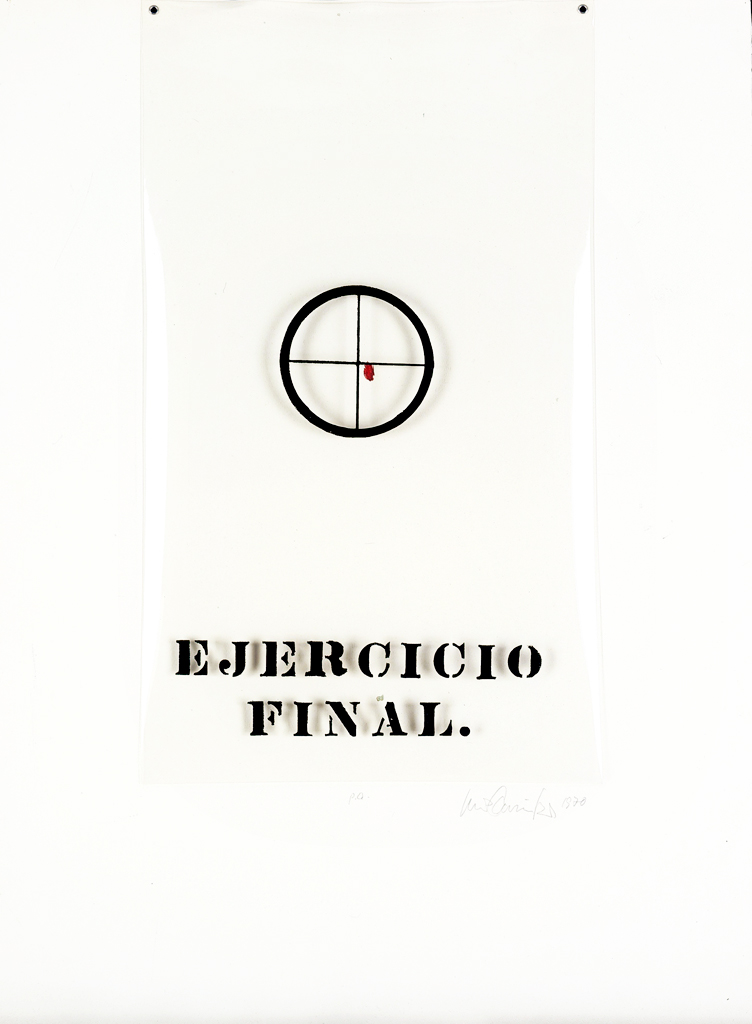

Stencil on painted surface

Graphite on paper, 7.25h x 11.25w x 6d in

Engraved brass plaque, laminated photograph, glass, and wood, Image: 13.5h x 10w x 2d in

Silver gelatin photograph in two parts, Image: 8h x 10w in

Etching, 24.5h x 24w in

Text, bricks and dirt, Dimensions variable

Luis Camnitzer

Maïs, courge et carotte :

ou comment renverser le rapport arbitraire entre image et langage

06/02/2014 – 25/03/2014

Guest curator : Florencia Chernajovsky

From 7 February to 20 March, Cortex Athletico gallery-Paris presents an exhibition that brings together, for the first time in France, an ensemble of works from key periods of the career of Uruguayan artist Luis Camnitzer. Taking the complex link between image and text as a common thread, the exhibition takes its title from the subversive and absurd gesture of Simón Rodríguez, who, at the beginning of the 19th century, christened his three children with names of vegetables and not saint’s names as Catholic tradition required.

Known mainly as the tutor of Simón Bolívar, the ‘liberator’ of Latin America, Simón Rodríguez had, like Luis Camnitzer, a strong commitment to politics and pedagogy. Rodríguez (1769-1854) was an educator and a utopian philosopher who, through a series of publications, created a teaching theory that remains revolutionary to this day. In 1797, he was forced to leave Venezuela for political reasons, living an emigrant’s life before coming back to Latin America, as ‘Director of Education, Science and Culture’ for the Bolivian Republic.

Very engaged with education and pedagogy in art, Luis Camnitzer occupied the role of pedagogical advisor on several occasions. Born in Lübeck in 1937, his family left to Uruguay when he was one year old. He grew up in Montevideo, where he received his degree in art and studied architecture, and emigrated to New York at the age of 27, where he still lives today. For the last five decades, since the end of the 1950s, Camnitzer has practiced as an artist, essayist, pedagogue, teacher, exhibition curator, theoretician and art critic.

Luis Camnitzer’s interest in Simón Rodríguez is both educational and political. Whilst willingly referring to European artists such as Magritte or Mallarmé, Camnitzer insists on the importance of Simón Rodríguez as a tutelary figure in the historicisation of conceptualism in Latin America. “Rodríguez made me realise that I came from a distinct genealogy, one that helped me understand Magritte and Mallarmé, without depending on them”[1], he says.

Incidentally, Camnitzer claims that the visual layout of Rodríguez’s texts is a prototype for conceptualist art and anticipates Mallarmé’s graphic poems. Like Camnitzer, Rodríguez was concerned bywith the erosion process of information that happens through communication. “Simón Rodríguez was interested in how to communicate without a loss of information. He outlined his thoughts with a graphic design that allowed him to clarify his message,” explains Camnitzer.

Going from prints on paper made with what was at hand in the 1960s with the ‘New York Graphic Workshop’, to the works in volume of the last few years, the exhibition recounts Luis Camnitzer’s historical career, exploring the way his work constantly questions the links between visual art and language.

In Camnitzer’s work, words and things are presented to demystify and freely reconfigure the world that surrounds us. With works like the series entitled Dictionary (1969-1970), the artist humorously mixes possible combinations, bringing together graphic signs and words. Thus, a circular pictogram encompasses a cylinder, as well as a zero, a circumference, a cupola or a ball. “I discovered that a written description of a visual situation was as efficient as an image, if not more,” says Camnitzer. Inescapably referring to the games of free association between images and language of René Magritte in his famous painting Ceci n’est pas une pipe and his illustrated text Les Mots et les images (1929) amongst others, Camnitzer pursues the subversion of the arbitrary links between the signified and the signifier.

At the start, the choice of printmaking as a medium showed Camnitzer’s political wish for the democratisation of art through printing. An agitator at heart, he frequently tackles the standards dictated by the art market, selling his own signature by the centimetre for example, or in slices, or his self-portrait created mechanically with the help of a fan. The photo-engraving technique allows Camnitzer to bring image and text to the same level, integrating representations of oppression, torture and violence of the political situation in Latin America. The political dimension of his work is even more efficient because it’s only suggested.

To sum it up in the artist’s own words: “Language interests me as a means but also as a model. I was interested in the immutability of classification: why do things have prescribed names that therefore substitute and eclipse a certain reality with a layer of literature? I know there are practical reasons, but I liked this speculation… In 1978, I combined in an arbitrary manner twenty small found objects with twenty titles that were written down on bits of paper beforehand. I proposed chaos and the public projected their own symbolisation to create a narrative order, accusing me of having imposed it myself. This piece was important to me because it allowed me to discover the power of evocation.”

Florencia Chernajovsky

February 2014

With a Masters in Theories and Practices of language and arts at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Florencia Chernajovsky conducted her research on conceptualism in Latin America under the direction of Patricia Falguières. She has been head of research at the Centre Pompidou since 2010 and has worked for the ‘Contemporary and prospective creation’ department for the exhibition Danser sa vie, and for the Pierre Huyghe retrospective. She is currently in charge of the general oordination and research of the Nouveau Festival of the Centre Pompidou alongside with Bernard Blistène. She recently curated an exhibition of Nicolás Bacal and Pablo Accinelli at Level One at gb agency gallery in Paris.